There are many nutrients that our bodies demand higher quantities of during pregnancy and postpartum — and iodine is one of them!

Iodine is a key mineral that supports not only thyroid health, but ovarian health, breast health, fetal brain development, and more! You may not have heard much about this mineral, until now, but it’s definitely one we should keep on our radar in our reproductive years.

In this blog, I’ll share the implications of iodine for when you may be trying to conceive, during pregnancy, and during lactation. Plus, I’ll review how you can tell if you’re getting enough iodine and ways to improve your iodine intake.

Let’s dive in!

Iodine: Why this mineral is essential for fertility, pregnancy, and lactation

Iodine for Fertility

When it comes to female fertility, iodine supports thyroid health and ovarian function. Research indicates that “iodine is taken up avidly by the ovary and endometrium” and may support implantation. This isn’t just true for humans but is seen in animals, too. In animals, iodine supplementation is frequently used to restore ovulatory function.

Iodine deficiency is a widely recognized risk factor for pregnancy loss, and maternal and neonatal thyroid problems. When you’re trying to conceive, prioritizing iodine is something you can focus on to support your overall fertility and your health during pregnancy.

You may have heard that most developed countries don’t have an iodine deficiency problem, thanks to public health initiatives that fortify table salt with iodine.

But that doesn’t mean that all women are receiving adequate amounts of iodine with these public health measures — they are merely avoiding more severe forms of deficiency. Studies show that insufficient iodine levels are actually quite common — 44% of women in developed countries have insufficient iodine levels. This is concerning, as insufficient iodine is associated with delays in conception among couples who are actively trying to conceive.

In a study looking at time to conception among women in America and Europe, women with low urinary iodine levels had a 46% reduction in fertility. A closer look at the study revealed that 28% of the iodine-deficient group were unable to conceive within one year, whereas this rate was only 12.5% in the iodine-sufficient group.

Requirements for iodine increase in pregnancy and breastfeeding, so optimizing iodine intake before you conceive is also helpful in preparation for these coming stages. (You can learn more about iodine and fertility in my book, Real Food for Fertility.)

Iodine for Pregnancy

Iodine needs increase during pregnancy, yet many women do not consume enough iodine during pregnancy to keep up with this demand.

The World Health Organization (WHO) recommends ≥ 250 mcg of iodine each day. In the US, there are two separate iodine recommendations for pregnancy: the recommended dietary allowance (RDA) of 220 mcg/day (which is assumed to meet 97.5% of the pregnant population’s needs) and the estimated average requirement (EAR) of 150 mcg/day (which is assumed to be sufficient for 50% of the pregnant population).

A recent study looked at the iodine intake of 750 pregnant women in the U.S. The average iodine intake from food alone was only 109 mcg/day. As you can see, that’s much less than the WHO recommendation, RDA, and even the EAR.

This study found that 63% of participants consumed less than 150 mcg a day of iodine from their diet. Most women (65%) took a supplement containing iodine, but only one-third were getting ≥150 mcg/day from their supplement. Iodine supplementation increased iodine intake, but even with supplementation 41% of study participants still remained below the estimated average requirement (EAR) of 150 mcg/day.

Low iodine intake levels are a problem in other countries, too. A 2020 study out of Norway looked at iodine intakes in over 78,000 pregnancies. Shockingly, from food intake alone, only 4.6% of pregnant women reached the WHO’s recommendation of ≥ 250 mcg/day of iodine.

This study also found higher rates of pregnancy complications in those who under-consumed iodine. Women with low iodine intake of <100 mcg/day had a significantly higher risk of preeclampsia, intrauterine growth restriction, and preterm delivery. Intake below 150 mcg/day was associated with having a lower birth weight infant, likely related to iodine’s role in thyroid health and fetal growth and development.

Iodine is essential for maternal thyroid function and the 50% increased demand for thyroid hormone during pregnancy. Iodine is also necessary for normal thyroid function in babies, too.

And if you weren’t sold yet on iodine’s importance, it is also essential for healthy brain development. According to the Journal of the American Medical Association, “Iodine deficiency remains the leading cause of preventable intellectual disability worldwide.”

Since low iodine intake is a major risk factor for maternal hypothyroidism — and because hypothyroidism is a major risk for early pregnancy loss — sufficient iodine intake is especially important in early pregnancy.

Iodine for Lactation

Iodine concentrates not only in the thyroid gland but also in the breasts. As breasts change during pregnancy in preparation for lactation, the demand for iodine to support breast health also increases. It’s well-known that dense, painful, and fibrocystic breasts are associated with iodine deficiency (and iodine supplementation often improves these conditions). I dive into the data on this in Real Food for Fertility.

Iodine requirements during lactation are high, but current dietary intake recommendations are poorly defined and vary substantially between countries. In the US, the RDA for iodine during lactation is 290 mcg/day. This is a bit higher than the iodine RDA for pregnancy to account for the iodine that will be transferred into breast milk.

During lactation, iodine status is best assessed by breast milk iodine concentration (BMIC). The iodine concentration in breast milk strongly depends on the maternal iodine intake, especially in the hours preceding breastfeeding. Therefore it is difficult to determine an optimal threshold.

One study noted: “There exists no consensus on optimal BMIC, in large part because of the debate over iodine requirements of infants. Measured concentrations of iodine in breast milk vary ≤100-fold on the basis of maternal diet, environmental factors enhancing or inhibiting iodine availability in the food supply, salt iodization, maternal supplementation, and measurement inaccuracies.”

For exclusively breastfeeding infants, human milk is the only source of iodine, so if mom doesn’t have enough, neither will the baby. Iodine is a key nutrient for thyroid function, and since the thyroid undergoes substantial changes during the first year postpartum, having an adequate intake is equally crucial for mom’s health.

Unfortunately, iodine deficiency is quite common among breastfeeding moms, despite public health programs like salt fortification. In one study from New Zealand, 87 breastfeeding mother-infant pairs were recruited at 3 months postpartum. In this cohort, the average urinary iodine concentration was below WHO cut offs, indicating deficiency. Likewise, infant iodine status was also compromised, with average urinary iodine concentrations falling below normal levels.

When they looked at the women’s iodine intake (including supplements), 58% were below the New Zealand EAR of 190 μg/day, and median intake fell below the New Zealand RDI of 270 mcg. Median iodine intake for women using iodine-containing supplements was higher, but came in just above the lower cut-off of the RDIl.

A recent study on the prevalence and predictors of breast milk iodine concentrations found that the dietary pattern that breastfeeding women were following strongly predicted whether her milk was likely to have enough iodine for her baby’s needs or not.

Low iodine concentrations were found in more than half of the women, but deficiency was both more common and more severe in women who followed plant-based diets. Breast milk from vegan and vegetarian women often contained too little iodine to meet the requirements for infants of 0–6 months of age —75% of vegan mothers and 67% of vegetarian mothers had breast milk that was deficient in iodine. Later in this article, when you read the section on food sources, you’ll understand why this is the case.

Iodine status in lactating women and infants varies considerably worldwide. Mild iodine deficiency and excess iodine intake may likely be widespread, but quality data are limited. The impact on child development is also uncertain.

Salt iodization is the primary public health intervention to prevent iodine deficiency and provide adequate iodine nutrition, but as studies have shown, it’s often not enough. In populations with poor inclusion of iodized salt and low iodine intake, iodine supplementation or a greater focus on natural food sources of iodine may be needed.

How do you know if you’re deficient in iodine?

Some common symptoms of iodine deficiency are: the presence of cystic tissue (including ovarian cysts, fibrocystic breasts, and breast lumps), breast tenderness (particularly in your luteal phase), irregular or anovulatory menstrual cycles, thyroid abnormalities, and poor immune function. But the only way to truly know if you are deficient is to test.

Determining whether or not you may need additional iodine supplementation can be challenging. For one, iodine content is rarely listed on products or nutrient databases, and levels can vary relative to how and where the food was grown or raised. This makes tracking iodine intake accurately a challenge. Second, testing for iodine deficiency is not routine, making the determination of who needs more iodine — and how much — more difficult. Some functional medicine practitioners are more familiar with iodine testing.

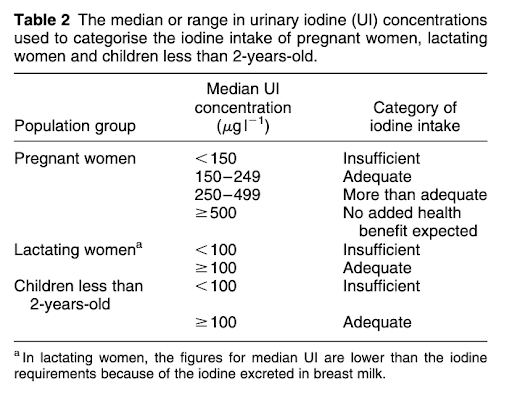

Iodine status is most commonly assessed by measuring urinary levels of the mineral; this is called Urinary Iodine Concentration or UIC. Low urinary iodine levels of <150 mcg/L indicate iodine deficiency. UIC levels between 150 and 249 mcg/L indicate adequate consumption of iodine. Levels of 250-499 mcg/L reflect more than adequate consumption.

Some practitioners also use an iodine loading test (a urine test done following the administration of iodine supplements), however, this method is controversial to use during pregnancy.

In breastfeeding women, some research has found that breast milk iodine concentrations (BMIC) are a more reliable indicator of iodine status than urinary iodine concentrations. A 2022 systematic review on using BMIC to measure iodine status found that it’s “a promising biomarker of iodine status in lactating women and children <2 years of age.” Research has found that in iodine-sufficient areas (as confirmed by sufficient urinary iodine concentrations), median BMIC ranges from 150 and 180 mcgg/L. Keep in mind that testing breast milk levels is not as common among clinicians and may require a specialty lab. This means it’s usually reserved for use in research studies rather than the general population.

How much iodine do I need per day?

As mentioned earlier, the RDA for iodine is 220 to 290 mcg during pregnancy and lactation (though the World Health Organization recommends 250 mcg for pregnancy), and 150 mcg for the general population. It’s important to know that estimates of iodine needs are conservative, and those who are deficient may need higher levels for repletion. Average iodine intake from food is often below the recommended level, particularly for people who don’t consume seafood, dairy, and eggs.

Interestingly, in some parts of Asia, where consumption of seaweed and other iodine-rich seafood is common, iodine intake can be 5 to 100 times higher than in a typical Western diet. In Japan, average iodine intake is estimated to be 1,000 to 3,000 mcg per day. Some seaweed-containing soups have up to 7,750 mcg per 8 oz serving, and yet no adverse effects on pregnancy outcomes have been observed from higher intakes., For most of us, iodine deficiency is a bigger concern than getting too much.

I am of the opinion that iodine is a misunderstood nutrient and that our RDA may be set too low to meet iodine requirements for many individuals, as evidenced by widespread iodine deficiency, even among women meeting or exceeding intakes of 150 mcg/day (the non-pregnant RDA). This is why I encourage you to eat iodine-rich foods and also to explore testing your iodine status to see where you’re at.

Naturally, this leads us to a discussion on iodine-rich foods.

What are the best food sources of iodine?

Thankfully, there are many food sources of iodine. Seafood (especially seaweed), eggs, and dairy products are the most concentrated sources.

Consuming seaweed, scallops, cod, shrimp, sardines, and salmon is a great way to meet iodine needs. These foods are high in iodine, but also high in other nutrients that are needed in your reproductive years, like DHA, vitamin D, zinc, and selenium.

For women who do not consume seafood, dairy products, and eggs are the most important food sources of iodine. Many people dismiss the contribution of non-seafood items to iodine status, but a study out of Taiwan found that dairy consumption had a major impact on whether breastfeeding women had sufficient iodine levels in their milk. Women who didn’t consume dairy were 24 times more likely to have low iodine levels in their milk.

Other foods that contain iodine include asparagus, beets, cranberries, and of course, iodized salt. But, as I mentioned earlier, iodized salt helps, but it isn’t enough! Be aware that the iodine from iodized salt declines with storage, especially in high-humidity areas, so it’s not always a reliable source.

Some foods contain compounds called goitrogens that block the uptake of iodine in the thyroid gland. It’s wise to avoid soy products for this (and for several other reasons, as outlined in Chapter 4 of Real Food for Pregnancy and in Chapters 4 and 5 of Real Food for Fertility). If you have known thyroid problems, you may also want to limit your intake of raw cruciferous vegetables (such as cabbage, kale, and broccoli), as these contain goitrogens. Luckily, cooking or fermenting cruciferous vegetables circumvents this problem. In practical terms, this means you’re probably fine enjoying cooked broccoli, kale, or cabbage (or fermented cruciferous veggies, like kimchi or sauerkraut), but caution with regularly putting kale in smoothies or noshing on raw broccoli. Serving size and frequency of consumption make a difference, too!

Certain chemicals can also interfere with iodine metabolism, particularly halogens — chlorine, fluorine (or fluoride), and bromine. Some common chemicals, such as stain-resistant and non-stick chemicals (which contain fluorine) and flame retardants (which contain bromine) can be problematic for iodine status as well as thyroid function. This makes iodine repletion even more important for individuals who have been exposed to excessive levels of these chemicals. I go into more detail on avoiding toxins in both Real Food for Pregnancy and Real Food for Fertility, with the research to support why avoiding these toxins is important to health during pregnancy and in the preconception phase, respectively.

A note for those following a vegetarian or vegan diet

While iodine can be obtained from plant foods, many vegetarians and vegans do not meet their iodine needs. In a study from the UK, the average iodine intake was compared among women following different dietary patterns. Iodine intake was a shockingly low 24 mcg among vegan women, 91 mcg for vegetarians, and 113 mcg for omnivores. While all groups come up short on dietary iodine (remember, the RDA is 150 mcg for non-pregnant women), vegan women are the most significantly affected. Likewise, studies from both the United States and Europe show significantly lower urinary iodine concentrations in vegans compared to omnivores.

This is because the next best sources of iodine (after seaweed) are seafood, eggs, and dairy products. As more people consume vegan, vegetarian, or plant-based diets, iodine deficiency is now plaguing parts of the world that traditionally had no widespread issues.

Take Iceland as an example. The rates of iodine deficiency have skyrocketed in recent years as more women are ditching their traditional eating patterns of fish, dairy, and eggs. Icelandic women who avoid fish have the most severe cases of iodine deficiency. In Switzerland, both vegetarian and vegan women have been observed to be deficient in iodine (with more severe deficiency seen in vegans).

If you include eggs and dairy in your diet daily, you’re much more likely to meet your iodine quota. But, if you don’t consume eggs and dairy (or seafood) regularly, including a source of seaweed in your diet is an absolute necessity to avoid an iodine deficiency.

What about iodine supplementation?

While I encourage food sources of iodine and a prenatal or multivitamin that contains iodine, some women will require a separate supplement, especially those who do not eat enough seafood, eggs, and dairy. Sadly, about half of all prenatal vitamins fail to include iodine at all (according to a survey of 223 prenatal vitamins available in the United States). For vegans, regular inclusion of seaweed (or an iodine supplement) would be essential.

While intake of iodine above the RDA is controversial, numerous professional organizations recommend a supplement with a minimum of 150 mcg of iodine per day during preconception, pregnancy, and lactation. This includes the American Thyroid Association, European Thyroid Association, Endocrine Society, the American Academy of Pediatrics, and several others. Many practitioners note that iodine intakes above the RDA are required by their clients, particularly when they are iodine deficient.

The prenatal vitamins that I recommend (FullWell and Seeking Health) meet the needs of pregnancy. If your clinician determines you need extra, I link out to some options in my Fullscript (click the recommendation tab at the top > Shared Protocols).

Iodine works in synergy with other nutrients

As with all nutrients, iodine has synergistic effects with other vitamins and minerals. These include (but are not limited to), selenium, iron, zinc, vitamins A, C, D, and E, as well as B vitamins. It’s important that iodine supplementation (particularly at higher doses) be implemented alongside sufficient intake of these nutrients. If you are planning to supplement with a higher dose of iodine, work closely with your healthcare provider.

Summary

Iodine is a critical nutrient for fertility, pregnancy, and lactation. Yet, many women are consuming insufficient levels of iodine, putting them at risk for fertility and pregnancy complications. In summary:

- More than half of Americans do not consume enough iodine, despite salt iodization.

- Iodine supports ovarian health, and insufficient intakes are associated with delays in conception.

- Iodine needs increase in pregnancy, and insufficient intakes can significantly increase a pregnant woman’s risk of miscarriage, preeclampsia, intrauterine growth restriction, and preterm delivery.

- Iodine is essential for thyroid function and is an important part of brain development for baby.

- Iodine needs increase even more during lactation, as breastfeeding infants receive iodine solely from breast milk.

- Cystic tissue, breast tenderness, irregular or anovulatory menstrual cycles, thyroid abnormalities, and poor immune function are symptoms of iodine deficiency. The only certain way to know of a deficiency is to test.

- The iodine RDA for non-pregnant women is 150 mcg/day. The iodine RDA for pregnant women is 220 mcg/day, yet the WHO recommends ≥ 250 mcg/day. Recommended amounts vary country to country.

- The best food sources of iodine are seaweed, seafood, eggs, and dairy.

- Iodine has synergistic effects with other vitamins and minerals. Eating nutrient-dense foods will help increase iodine intakes and its effects with other nutrients.

What are your favorite ways to consume seaweed and seafood? Comment below.

Until next time,

Lily

PS – Have you picked up a copy of Real Food for Fertility yet? Compared to all of my other books, this is the most data-packed of them all, featuring information from over 2,300 studies. We’ve been so grateful to receive such positive feedback on the book and I hope you love it too. You can download the first chapter for free from the book website, and grab a copy on Amazon.

References

- Mathews, D.M., et al. “Iodine and fertility: do we know enough?” Human Reproduction 36(2) (2021): 265–274.

- Sarkar, A.K. “Therapeutic management of anoestrus cows with diluted Logul’s iodine and massage on reproductive organs — uncontrolled case study.” Research Journal of Animal and Veterinary Sciences 1(1) (2006): 30–32

- Toloza, F.J.K., et al. “Consequences of severe iodine deficiency in pregnancy: evidence in humans.” Frontiers in Endocrinology 11 (2020): 409.

- Zimmermann, Michael B. “The effects of iodine deficiency in pregnancy and infancy.” Paediatric and Perinatal Epidemiology 26.s1 (2012): 108-117.

- Griebel-Thompson, Adrianne K., et al. “Iodine Intake From Diet and Supplements and Urinary Iodine Concentration in a Cohort of Pregnant Women in the United States.” The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition (2023).

- Stagnaro-Green, Alex, Scott Sullivan, and Elizabeth N Pearce. “Iodine supplementation during pregnancy and lactation.” JAMA 308.23 (2012): 2463-2464.

- Aceves, C., et al. “Is iodine a gatekeeper of the integrity of the mammary gland?” Journal of Mammary Gland Biology and Neoplasia 10(2) (2005): 189–196

- Ghent, W.R., et al. “Iodine replacement in fibrocystic disease of the breast.” Canadian Journal of Surgery 36(5) (1993): 453–60.

- Lazarus, John H. “The importance of iodine in public health.” Environmental Geochemistry and Health 37(4) (2015): 605-618; Milagres, R.C.R.M., et al. “Food Iodine Content Table compiled from international databases.” Revista de Nutrição 33 (2020).

- WHO Secretariat, et al. “Prevention and control of iodine deficiency in pregnant and lactating women and in children less than 2-years-old: conclusions and recommendations of the Technical Consultation.” Public health nutrition vol. 10,12A (2007): 1606-11.

- Ristic-Medic, D., et al. “Methods of assessment of iodine status in humans: a systematic review.” The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 89(6) (2009): 2052S-2069S

- Flechas, J.D. “Iodine supplementation and monitoring to ensure patient health and safety.” Journal of Restorative Medicine 1(1) (2012): 49–55

- Fuse, Y., et al. “Studies on urinary excretion and variability of dietary iodine in healthy Japanese adults.” Endocrine Journal 69(4) (2022): 427–440.

- Liu, Shuchang, et al. “Breast Milk Iodine Concentration (BMIC) as a biomarker of iodine status in lactating women and children< 2 years of age: a systematic review.” Nutrients 14.9 (2022): 1691.

- Zava, T.T., and D.T. Zava. “Assessment of Japanese iodine intake based on seaweed consumption in Japan: a literature-based analysis.” Thyroid Research 4(1) (2011): 1–7.

- Fuse, Yozen, et al. “Iodine status of pregnant and postpartum Japanese women: effect of iodine intake on maternal and neonatal thyroid function in an iodine-sufficient area.” The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism 96.12 (2011): 3846-3854.

- Huang, Chun-Jui, et al. “Iodine Concentration in the Breast Milk and Urine as Biomarkers of Iodine Nutritional Status of Lactating Women and Breastfed Infants in Taiwan.” Nutrients 15.19 (2023): 4125.

- Diosady, L. L., et al. “Stability of iodine in iodized salt used for correction of iodine-deficiency disorders. II.” Food and Nutrition Bulletin 19.3 (1998): 240-250.

- BaJaJ, Jagminder K., Poonam Salwan, and Shalini Salwan. “Various possible toxicants involved in thyroid dysfunction: A Review.” Journal of clinical and diagnostic research: JCDR 10.1 (2016): FE01.

- Fallon, N., and S.A. Dillon. “Low intakes of iodine and selenium amongst vegan and vegetarian women highlight a potential nutritional vulnerability.” Frontiers in Nutrition 7 (2020): 72.

- Kristensen, N.B., et al. “Intake of macro-and micronutrients in Danish vegans.” Nutrition Journal 14(1) (2015): 1–10; Leung, A.M., et al. “Iodine status and thyroid function of Boston-area vegetarians and vegans.” J Clin Endocrinol Metab 96(8) (2011): E1303–E1307.

- Gostas, D.E., et al. “Dietary relationship with 24 h urinary iodine concentrations of young adults in the mountain west region of the United States.” Nutrients 12(1) (2020): 121

- Pehrsson, P.R., et al. “Iodine in foods and dietary supplements: a collaborative database developed by NIH, FDA and USDA.” Journal of Food Composition and Analysis (2022): 104369.

- Brownstein, D. (2008). Iodine: Why You Need It, Why You Can’t Live Without It. Arden, NC: Medical Alternatives Press.

- Adalsteinsdottir, S., et al. “Insufficient iodine status in pregnant women as a consequence of dietary changes.” Food & Nutrition Research 64 (2020).

- Schüpbach, R., et al. “Micronutrient status and intake in omnivores, vegetarians and vegans in Switzerland.” Eur J Nutr 56(1) (2017): 283–293.

- Combet, E., et al. “Low-level seaweed supplementation improves iodine status in iodine-insufficient women.” British Journal of Nutrition 112(5) (2014): 753–761.

- Leung, Angela M., Elizabeth N. Pearce, and Lewis E. Braverman. “Iodine content of prenatal multivitamins in the United States.” New England Journal of Medicine 360.9 (2009): 939-940.

- Lee, S.Y., and E.N. Pearce. (2018). “Iodine requirements in pregnancy.” Handbook of Nutrition and Pregnancy. Cham: Humana Press, 51–69.

Thank you so much for doing and sharing this research <3

You’re so welcome, Alexandra!

I have a theory that supplementing Iodine during my pregnancies have prevented morning sickness. For both 1st trimesters of my pregnancies I was supplementing Iodine from sea kelp daily, went through a 3 day period of missing the supplements and then experiencing intense morning sickness, which went away once I started supplementing again.

Interesting observation!

Thank you for another excellent article. An easy way I use to add seaweed to my food is it to put it in soups and broth. The seaweed flavour is not apparent and the broth can then be used for other meals.

Yes, that’s a great option. I often add a small piece of dried kombu or some wakame to broths or when cooking a pot of beans (from dried).

Here in New Zealand, midwives prescribe 150mcg iodine supplements during pregnancy. Unfortunately, nobody ensures that mothers continue to receive the supplements while breastfeeding. Our soil is very low in iodine so all plants here contain negligible amounts of iodine so the likelihood is that even with 150mcg extra, the majority of Kiwi mums are deficient. Seaweed is only a regular part of our diet for those who like (and can afford) sushi. I’d be interested to hear of other ways to incorporate seaweed into ones diet.

Nori seaweed snacks are a good option; it doesn’t have to be in sushi. Dried seaweed can be purchased from an Asian market or online. A bag will last for quite a long time. You can add a small chunk of kombu, for example, to broths or soups. Some also like added some dulse flakes to their salt to add a boost of iodine and trace minerals to other meals.

But don’t think seaweed is the only way to get iodine. Remember seafood of all kinds, eggs, and dairy are also good sources.

You mentioned Chlorine and Fluoride are chemicals that can interfere with Iodine. I know I’m on city water – although we recently just got an RO with remineralization, but I’m assuming that having those chemicals in our water doesn’t help?

Yes, a water filter is a good idea when your municipal water is chlorinated and fluoridated.

My grandpa told me he eats a half-sheet of nori every morning with eggs and bacon (only sometimes with a bit of rice), to prevent diabetes and thyroid problems. I picked up the habit as a baseline, plus eat other seaweeds as snacks and seasonings. Shrimp poached in butter-turmeric-salt water makes an easy breakfast! And I love a can of olive-oil packed sardines or salmon with sauerkraut and sprouted pumpkin seeds for lunch.

Nice work!

Such an interesting and informative post! Thank you! I’m 13w pregnant with my second and still breastfeeding my 3yo and my TSH came back 6.14. An endocrinologist wanted to put me on a pretty high dose thyroid medication, but I don’t feel comfortable. Therefore, I’m adding seaweed to my daily diet, plus 3 eggs, and my seeking health optimal prenatals. Hoping these help the situation. Is there a daily intake estimate for a pregnant and lactating person? Thank you again!